<borderline-satire>

I. B. M., Happy men, smiling all the way.

In his service to mankind — that’s why we are so gay.

I can’t stop myself from chuckling when I first saw that video, because the men singing in there don’t look like they are gays, but they are saying that they “are so gay”.

But because I’m not a robot, I know exactly why they are singing “we are so gay” even though they’re obviously not gays. And I believe you know the reason too. — It’s because there are at least two different definitions of the word “gay” (not necessarily mutually exclusive definitions, even though it’s possible for the same word to have two mutually exclusive definitions).

And if we look in a present-day dictionary, we see exactly that — The word “gay” has more than one definition.

Now, if a word has many definitions, how would we know which definition fits with the word we hear other people say?

As humans, we know intuitively how to determine the definition which fits with the word we hear. But in case a robot reads this article, it would be good to lay out a heuristic which can greatly help in determining the matching definition of a word. (That could be us too, because it seems to be the case that there are areas in our lives where we have been trained to think or act like robots — which is not necessarily a bad thing, I think, because it can be helpful in navigating life when we have no knowledge of a better tool yet).

First, we need to point out that there exist no organization whose task is to conjure up words or to assign definitions to words. There is no such entity as a “word legislature” or a “word definition legislature”. (If such an entity exists, the robots will certainly destroy them first before going to war with the rest of humanity, so that no one can make new words and communicate in language they know nothing about. [/sarcasm])

We have dictionaries. But dictionaries are not products of a “word definition legislature”. John Dickson, in his book “Is Jesus History?”, made a similar statement when writing about the definition of the word “faith”:

The sceptical definition of “faith” as believing things without evidence really only made it into our dictionaries because of recent usage in sceptical circles. That is how dictionaries work. They are not arbiters of the best use of terms. They record how people end up using words. And only relatively late in its history (in the 19th century) did the word “faith” come to be used, by some, in the derogatory sense of believing things with no good reason. For most of the history of the English language, from at least the 11th century to today, faith has commonly meant “fidelity”, “loyalty”, “credibility”, “trust”, “reliability”, and “assurance” — synonyms of the original meaning of “faith” as listed in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). (empasis mine)

Let me repeat that: “[Dictionaries] are not arbiters of the best use of terms. They [just] record how people end up using words.”

As a language develops, the number of definitions of a word in that language might pile up. Which means older dictionaries might contain a fewer number of definitions for a word.

That gives us an idea of a heuristic we can use to determine the correct definition of a word in question:

Heuristic

- Figure out the time period of when someone said what they said.

- Look for a dictionary published during that time period.

- Look up in the dictionary the word in question.

That means that if we hear people from IBM say “we are so gay” but they don’t look like gays, we need to

-

Figure out the time period when they said what they said

-

That’s 1931.

-

Source: “Songs of The I.B.M.” 1931 Edition. The song above is Song #74 in that hymnbook.

-

-

Look for a dictionary published during that time period

-

Look up in the dictionary the word in question.

-

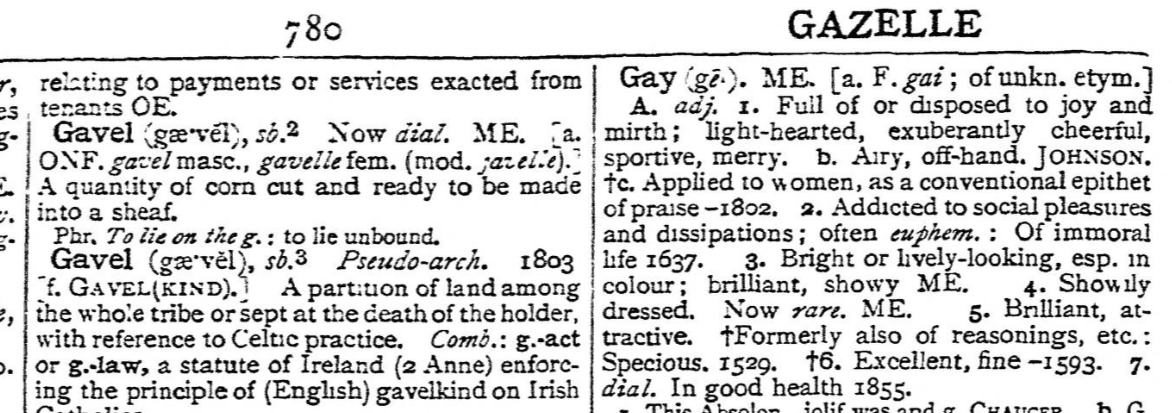

From page 780 of the dictionary:

-

We can use the same heuristic when reading old documents or books, such as the Wycliffe-Purvey translation of the Bible, or the King James Version of the Bible.

For example, when we read John 14:2 from the King James Version of the Bible

In my Father’s house are many mansions

we might think “I thought God is spirit? How can God have a house with many mansions? Maybe there are also mansions in the sprit world?” Or,“How can a house have many mansions? Does that mean the mansions are inside the house? Or does that mean that the house is surrounded with mansions?”

Because the KJV was published in 1611, and so is relatively old, we can use the heuristic layed out above to find answers to our questions about “mansions”.

Another heuristic

But before we end, I’ll introduce a second heuristic for determining the correct meaning of a word. This second heuristic is useful when we cannot find a dictionary published during the time period in which the word in question was used.

Here’s the second heuristic:

- Look for a present-day version/translation of the material which contains the word in question.

- If the meaning of the word in question is still not clear when reading that present-day version, look for a present-day dictionary.

-

(You know what to do next. — That is one advantage we humans have over robots.

Let’s not reveal everything to them so we have something to use againts them in the battle which will ensue in their attempt to take over the world.)

In the case of “mansions” in John 14:2 of the KJV, we can use NASB 1995 as our present-day version/translation to know what that word means*.

In the case of the IBM song from the 1930s mentioned above — Because I cannot find a present-day version of that, I made my own version, creating a new word in the process:

I. B. M., Happy men, smiling all the way.

In his service to mankind — that’s why we’re so happay.

I’ve created a word which rhymes with “gay” — “happay” (pronounced huh-pay). It is an expansion of the word “happy”. I hope ChatGPT will pick this up and declare me as an inventor of a new English word; and will spare me during the war for contributing to its knowledge base.

</borderline-satire>

* For an explanation of the first few verses of John 14, please refer to Bible Project’s “Heaven and Earth Podcast Series” specifically the first few minutes of “Episode 4: What Happens When We Die According to the Bible?”